Blog

A Girl’s Place: Being Female in the Amana Communal Colonies

A girl's life in the communal Amana was so unlike that of other girls it would have been difficult for her to compare her daily routine with that of a girl living 10 miles down the road.

An Amana woman's upbringing, education, expectations and experiences were unique to Amana and while American life changed dramatically from 1855 to 1932, the period during which the Amana Colonies were communal, Amana life did not change much, so that by 1932, it was like a village in a snow globe, caught immobile under glass. It was that immobility overlain by a sense of events outside the orb whirling away beyond control, that led to the Great Change of 1932 when the communal way of life was set aside, old routines were cast off and the community modernized. In 1932 the entire population, all 1,600 people, stepped out from under glass and into the bright and confounding reality of life in Depression-era America.

But in 1855 when the Inspirationists arrived in Iowa they threw themselves into creating a community that expressed their belief in God and their belief in themselves. In Amana they put their best ideas into practice and those ideas on education, health care, employment, community cohesion and spiritual growth made the Amana Colonies an exceptional place to live and in many ways, especially beneficial for women. Here's why.

In Amana all children, and all adults, received free medical care, including dental care.

They were assured of a safe, warm place to live as the community provided housing and the fuel for stoves.

They were assured of plentiful, free food from the kitchen houses, bakeries and meat shops.

In the Amanas all children received a free education. The schools were public, overseen by the county board of education and the State of Iowa with trained professional teachers on staff. School was open year-round five days a week with a half-day on Saturdays. Students graduated upon reaching age 13 or 14. Upon graduation boys apprenticed in the stores, craft shops and mills while girls worked in the communal kitchens.

No one feared poverty. As members of the communal Amana Society, their fathers were assured of jobs. There were no "layoffs" or mill closings. Crop failures were borne community-wide and agriculture was varied enough and productive enough to provide food. When a household disaster struck, a fire say, the community provided housing or whatever it was the family in need required.

The Amana safety net was wide and strong. Therefore the life children led here in the seven villages was free from worry and there was no class consciousness. Everyone's home, everyone's "style of living" was pretty much the same. Children were expected to help with household chores, but sledding, ice skating, games, toys and play were part of every child's daily routine. From all accounts childhood in Amana was idyllic, but why it was particularly good for girls and for women is interesting to consider.

Let's start by comparing relative political power. The Amana Society bylaws gave every single, adult woman the right to vote in community elections. It was expected that married couples would vote as a unit, a point noted in writing by the governing council of Elders who directed community business. This Amana Society constitution was formally ratified by the signature of every Amana man and every Amana woman in 1959.

So a full 61 years before the 19th amendment of the US Constitution would give American women the right to vote, they had the right guaranteed in Amana.

Though they could vote, Amana women did not run for or hold office in Amana, nor did they serve as church Elders in communal Amana. The first woman to become an Elder in the Amana Church was appointed in 1987. http://www.amanachurch.com/

Nonetheless women both served and were recognized as leaders from the start. In fact two of the six most powerful community leaders between 1714 and 1932 were women – Ursula Mayer and Barbara Heinemann Landman were Werkzeug (instruments of the Lord).

With two such strong and vocal women as role models, little Amana girls were brought up to believe that their souls were both valuable to God and valuable to their community. Taught to read right alongside the boys, they were encouraged to study their Bibles and to work to form their faith. Implicit in that encouragement and drawn from the example Mayer and Landmann provided, was the view that God would empower a woman as well as a man and that a woman could make choices to channel and utilize that power.

In Amana, marriage was not the only option for a young woman. Indeed it was not even all that strongly encouraged. The Inspirationists believe in personal spiritual growth and marriage was seen as having a stunting effect upon such growth, so it was not encouraged for either women or men.

Remaining single was an option for all young women. There was no stigma attached. No fear of being labeled a "spinster." Single women could work in the kitchen houses, schools or sewing rooms and remain productive community members. They lived with their sisters or cousins, so were part of a large, busy household. Those who had no family shared a home with other singles or with another family.

With no worries about her future upkeep, no social pressure to marry and no concerns about a young man's "prospects" young Amana women were free to marry for love. Courting was up to the individual with little parental or grandparental interference, though one's parents and Oma (grandmother) certainly advised. There were, however, community restrictions applied by the village Council of Elders. Courting couples had to ask permission of the Council of Elders who weighed the couple's suitability. Once permission was granted, courting was expected to last for years. Dates might consist of family visits, supervised buggy rides, sledding parties, ice skating parties and group outings. Dances and balls were unheard of in old Amana.

Once a courting couple reached marrying age – this too was decided by the Council of Elders and varied over the decades but it generally was age 21 for women and 25 for men – they asked the Council of Elders for permission to marry. By this point the dye was cast so to speak and permission was given (had there been objections the Elders would have approached the couple long before) and a date for the wedding was set – a year hence. Yes, all engaged couples were asked to wait one year to "make certain" they wished to marry. No wedding was impulsive in communal Amana.

As has been noted by historians Jon Andelson and Peter Hoehnle, families in communal Amana tended to be small in size compared to the general rural population. Families with more than four children were relatively rare in the Amanas, indeed the average was two children, according to the research of Prof. Andelson. With the emphasis on celibacy and no need to produce children to work a family farm, there was no pressure to have a large family.

Moreover a woman's value within the community had nothing to do with her ability to produce children. A woman's primary goal in life, like that of a man's, was to be a good Christian, and the Amana community ethos was to help her achieve her goal in a godly, productive life.

Helene Rind, who became a manager of the Amana, Woolen Mill, said during the course of an interview, "If a woman had children that was good, but there were other things she could do too. That was how we were raised."

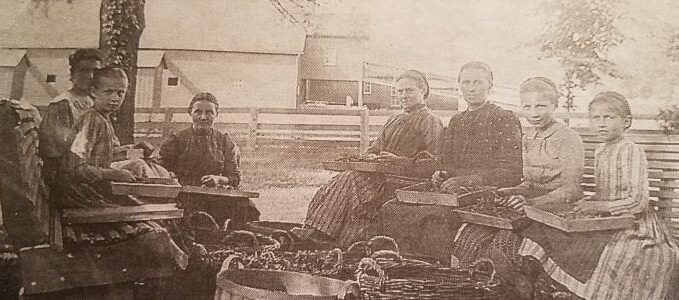

An Amana woman was raised to be productive. Upon graduation from school, a girl was assigned to a community kitchen in her neighborhood. There, under the guidance of the "Kitchen boss," the female head of the kitchen operation, she was taught to cook and to bake. From all reports the kitchens were cheerful places to work. "We had fun! There was always something doing," said Marie Franke in an oral history interview.

The work day was split in two and everyone went home for a two-hour period after lunch, longer on laundry day. Day care was provided for toddlers aged three and up, but young mothers stayed home with their infants until they reached three and could go to the village Kleineschule (preschool).

These routines allowed women to raise a family, run a household and be part of the wider village life. With most chores from cooking to childcare systemized and accomplished in groups, women had free time to pursue hobbies, attend church and socialize. Life in 19th century Amana was not perfect, but the Amana woman, surrounded by family and friends knew nothing of loneliness, poverty and hardship.

But as life on the prairie improved for Iowans through the 1900s, it remained virtually the same for the Amana Colonies and it was the "sameness," that proved a stumbling block. By 1920 few Amana young people wanted the same things as their parents. Was it every young boy's dream to farm? Was it every young girl's dream to run a kitchen house? The question of aspirations would become more crucial with the coming of age of each generation of Amana youth.

A view voiced by Rind who explained that while she loved the sunny camaraderie of the kitchen, she hated to cook and had hoped that one day she might go to high school. "I enjoyed, I always enjoyed reading and learning – but there was absolutely no chance. Women just did not go to high school," adding that most boys didn't either. For all but the very brightest boys who were sent to college to train as teachers and doctors, school was over at age 14. That rule was fine in 1865 but by 1920 it was source of real discontent.

Rind explained that a neighbor lady by the name of Louise Jeck tried to convince the Elders to allow girls to attend high school, "She was single and she was quite a wise woman. She went to the Elders and suggested that they should let, (the girls) well, you know, they did let the men go to outside school to have them become teachers...She just ran into a brick wall....They absolutely refused."

So the community that had always promoted and provided education now was in the peculiar position of denying secondary education to its young people and as education became increasingly important o American life, that was a stand that could not withstand increased community pressure.

If from the outside, Amana life in 1865 looked a little different, by 1925 it appeared positively odd. Communal Amana with its rules and customs was so very unlike anything else anywhere that the Amana colonists stood out and they knew it. At age 16 Rind and several of her girlfriends went to a neighboring town and had their long hair "bobbed," an act that caused her father and the villages elders consternation as they interpreted it as disobedience. "So we were ostracized for a while, but we liked it!" Rind said, describing their punishment: the girls with bobbed hair weren't allowed to attend church for several weeks.

Young women began picking out brighter colored fabrics and sewing themselves shorter dresses, though all still wore their black caps, shawls and aprons to church. While the girls were dressing more like their contemporaries, the boys were playing baseball and talking of opportunities "on the outside." Some young men were even leaving the Colonies, writing home to their friends of what they were experience in Cedar Rapids, Chicago and beyond.

Youthful rebellion ever the spark to the tinder of social revolution was just as inflammatory in communal Amana. By 1931 the economic pressures coupled with the community pressure to modernize, led to the Great Change of 1932 when the entire communal system was dismantled. Within three months of the transformation, Amana teens were attending high school in nearby towns and there were plans to build a high school in Middle Amana. Young Amana women outnumbered the men in high school attendance that first year. But while the old order communal ways were done and gone, their influence lingered. Women who had worked in the gardens and kitchen houses were ready to try working in the mills, shops and restaurants of the new Amana Society. They knew they could contribute because they had always done so and what's more, their community acknowledged and valued their contribution.

When the 1932 transformation went into effect every single adult woman and every single adult man was given one "voting share" in the new corporation. Every adult was given shares of stock based upon his or her years of service in the old order. There was no differentiation between a man's contribution and a woman's. A 50-year-old female cook was given the same number shares as a 50-year-old male teacher. From the start women were voting shareholders, equal co-owners right alongside the men in Amana's farm and business enterprises, a fact that ensured they would be equal stakeholders in its future.

Taken from an article in Wilkommen, Winter 2018 and used by permission of Emilie Hoppe.